- Home

- Michael McDowell

Wicked Stepmother

Wicked Stepmother Read online

Also Available by Michael McDowell

The Amulet

Cold Moon Over Babylon

Gilded Needles

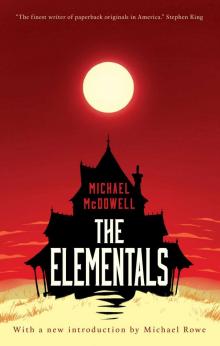

The Elementals

Katie

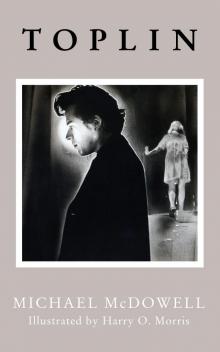

Toplin

Blood Rubies (with Dennis Schuetz)

WICKED STEPMOTHER

MICHAEL McDOWELL

& DENNIS SCHUETZ

(writing as Axel Young)

VALANCOURT BOOKS

Dedication: For Eric Shifler

Originally published by Avon Books in 1983

First Valancourt Books edition 2016

Copyright © 1983 by Michael McDowell and Dennis Schuetz

Published by Valancourt Books, Richmond, Virginia

http://www.valancourtbooks.com

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the copying, scanning, uploading, and/or electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitutes unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher.

Cover by Henry Petrides

In the winter a blanket of snow was laid over the grave, and when the sun lifted it off in the spring, the man married a second wife.

“Aschenputtel”

PART ONE: The Firstborn

1

On the twenty-second ring of the telephone, Verity Hawke Larner finally leaned over the edge of the bed and swatted the receiver off the cradle. She yawned dramatically, fumbled for the receiver, and answered in a drowsy—even catatonic—voice, “Hmmmmmmm . . .”

“Hello, Verity!” a cheerful female voice exclaimed on the other end.

Verity yawned again, cleared her throat, and accidentally dropped the telephone. Then she picked it up and pressed it to her ear. “What?” she whispered hoarsely.

“It’s me, Verity—Louise. I’ve been ringing and ringing.”

“I was here. I was asleep. It’s the middle of the night.”

“It’s one o’clock in the afternoon in Boston.” Louise’s voice was crisper now. “That means it’s noon in Kansas City. This is not the middle of the night. Open your blinds.”

Verity crawled out of bed and went to the window. With one crooked finger she pulled down a single slat of the Levolors. Searing sunlight flooded the room. “Oh, God,” cried Verity into the telephone, “you must be psychic! It is day!”

“Why aren’t you at work?” Louise demanded.

“No work today. Louise, why have you called?”

“You ought not sleep away your day off. I’ll bet there’s plenty of interesting things to do in Kansas City on a sunny afternoon.”

“How did you know it was sunny here?” Verity said after a pause. “You are calling long distance, aren’t you? I mean, you’re not in Kansas City, are you?”

“No, of course not, I’m at the office. Your father asked me to call. . . . I thought Saturday was your day off.”

“I have every day off.”

There was no commiseration in Louise’s voice when she asked, “Were you fired again?”—only surprise at the unvarying repetition of an old pattern.

Verity slid down into the pillows.

“No, I quit.”

Louise began a little sermon, the highlights of which were inflation, the job market, and the importance of a goal in life.

Louise played a double role in Verity’s existence. She was her widowed father’s business partner—in a real-estate agency that handled some of the most exclusive properties in Boston—and she was Verity’s mother-in-law. Three and a half years before, Verity had married Louise’s only son, Eric. Verity had been in Kansas City for two years; Eric was still in Boston.

Without interrupting her mother-in-law, Verity pulled her dark glasses from the drawer of the nightstand and put them on to cut the glare of the sunlight falling in strips through the opened Levolors. She looked at the man in bed beside her and tried to remember his name. “It starts with a B,” she murmured.

Louise’s lecture droned on.

“Blond hair,” Verity whispered, with her hand over the mouthpiece, staring with a creased brow at her sleeping companion. “Who do I know with blond hair?” Gently Verity pried open one of the man’s eyes: the iris was dark brown; she decided that the blond hair must be bleached. She cautiously lifted the sheet and peered beneath it. “Definitely bleached,” she concluded, then said to her mother-in-law:

“Job burnout, that’s why I quit. Do you know what job burnout is like?”

“Of course I do. Channel Five had a five-part series on the eleven o’clock news.”

“Then will you please stop with this inane lecture? If I need a lecture, I’ll call Father. If I want to be bored, I’ll call Eric.”

When her marriage to Louise’s son failed after only a year and a half, Verity arranged with the Hawke family lawyer to have separation papers executed. She withdrew what little personal funds she had in her savings accounts, climbed into her car, and drove west. She settled in Kansas City because that was where the car broke down. In two years she had had seven different jobs.

Verity slid out of the bed, grabbed a robe from a pile of clothes on her desk chair, and pulled it on.

“I hope you’re eating right, Verity. You shouldn’t get too thin—it makes you look haggard.”

“I look fine, Louise.”

Verity peered out of the window again. Her orange Lotus was angled up over the curb and onto the sidewalk in front of the apartment building. She looked back at the man in the bed, wondering whether he were responsible for that, or whether it had been her own doing.

“Louise,” said Verity, “is there a reason for this call, other than to annoy me?”

“Yes,” replied Louise, “I’m calling about your sister.”

Verity roamed into the kitchen, still with the receiver cradled at her ear.

“If it’s about Cassandra, why didn’t Father call?”

“Richard is out closing a deal this afternoon,” Louise said coolly, “and he asked me to speak to you. Besides, Verity, I’m part of your family too, you know.”

Verity opened the refrigerator and took out a carton of orange juice.

“All right, Louise, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to heap insults on your permanent wave. Now what about Cassandra?”

Verity flipped open the spout and took a long swallow straight from the carton.

“She was made managing-editor of Iphigenia this week.”

“Great,” said Verity impassively. “The entire readership of that magazine could sit down to dinner around a card table. Have you ever looked at that thing?”

“Of course I have. We have a complete run of it right here in the office.”

“Have you actually sat down and read it?”

“I skimmed a few of the issues that Cassandra edited,” Louise replied testily. “I don’t really understand poetry. The point is, Verity, your father thinks a little celebration is in order for Cassandra and he wants you here for it. He thinks two years is long enough to stay away. Besides, you haven’t proved a thing. Your brother wants to see you again too.”

“How is Jonathan?”

“Fine. So what’s your answer, Verity?”

Verity sat at the kitchen table, tracing a nail over the features of the leering orange face on the waxed juice carton.

“Well,” Louise persisted, “will you come home?”

“Sure,” said Verity at last. “I’ll come. It’s a good excuse not to look for another job. Besides,” she added after a moment, “I would like to see Father again. And Cassandra. And Jonathan. And—I guess that’s all.”

“Do you want

me to have one of the secretaries make plane reservations? What airlines fly out of Kansas City?”

“Don’t bother, I’ll be driving. It’ll give me a chance to stop in New York to see some old friends.”

“Just make sure you’re in Boston by the time of the party—it’s planned for the second. Oh, and as long as we’re on the subject, why don’t I ask your father to look around and see if he can find a position for you somewhere, something that—”

“Don’t bother!” said Verity sharply. “Why don’t you ask Father if he can find Eric a job instead?”

The man—whoever he was—walked in naked from the bedroom. Verity looked over her shoulder. He grinned, stretched, and yawned magnificently—it was more of a roar.

“What was that?” asked Louise.

“The dog,” said Verity.

“It didn’t sound like a dog.”

“The dog has a cold.”

“I didn’t know you liked pets. What kind is it?”

“Mongrel,” Verity replied dryly. The man reached for the orange juice; Verity snatched it away from him.

“Are you going to bring him with you?”

“He goes straight back to the kennel,” Verity replied. “I have to go, Louise. I’ll probably leave tomorrow. I may be in New York for two or three days, and then I’ll come straight on up to Boston. When is this party again?”

“A week from Saturday.”

“I’ll be there for sure. Give Father my love.”

Louise hung up without reply.

Verity turned to the man sitting across from her at the table.

“Have we been introduced?” she asked coldly.

On a balmy Sunday afternoon when the Japanese magnolias were in full bloom all over greater Boston, Verity Hawke Larner turned her orange Lotus into the horseshoe drive of her father’s home. Where the drive widened before the house, she was distressed to find no space available to park. She pulled slowly around, ticking off the family cars, frowning at Louise Larner’s lime-green Toronado, wondering at the unfamiliar yellow Cadillac. Verity reached the other end of the drive. She was about to turn into the street and park beside the cobblestone wall, when she suddenly changed her mind, shifted into reverse, and screeched backward over the gravel. She pulled to a stop right up beside her mother-in-law’s Toronado, braked, and turned off the ignition.

Verity pulled a small brush from the glove compartment and ran it quickly through her thick, medium-length sandy hair. Then she withdrew a small, square envelope of leather. Unsnapping this, she took out a vial of white powder and a tiny slender spoon. Leaning down over the passenger seat, she quickly and expertly scooped out two mounds of cocaine, and snorted them up. She replaced the envelope, then looked into the mirror, and dabbed with a wet finger at all the stray grains of the drug. From the glove compartment she took a tube of ruby lipstick and applied it lightly to her mouth. Then she brushed her cheeks with just enough rouge to provide a natural-looking flush. After that, she readjusted her large-framed dark glasses. She grabbed her red leather jacket from the front seat and got out, leaving her bags in the back seat for one of the servants. She passed by the unfamiliar Cadillac, and peered at the address on an envelope that had been left face up on the dashboard: the car belonged to Eugene Strable, the Hawkes’ friend and lawyer. Eugene Strable, Verity remembered, bought a new Cadillac every year.

The front doors of the house were unlocked. Verity slipped inside and closed them quickly behind her. Mechanically, she dropped her keys in the basket on the marble half-table in the foyer. She stopped and listened as she checked her outfit before going farther into the house. She wore black wool trousers tapered at the ankles and a red silk mandarin-style blouse beneath her red leather jacket. A gold chain rested about her neck, and more gold shone in the woven belt wrapped about her slender waist. Given the number of cars in the driveway, the house was curiously quiet. After a moment, Verity realized that the slight hum she heard was the sound of muted voices at the back of the house. She opened the door of the living room, walked its length, wondering a little at its consummate neatness, then stood at the closed doors of the formal dining room.

When Verity cocked her ear toward the doors, she could make out her sister Cassandra’s voice, then Eugene Strable’s—but why was everyone in the dining room at three o’clock in the afternoon? “My God,” she murmured, “I’ll bet they’ve waited luncheon on me!”

Verity took a deep breath—drawing a little more of the calming cocaine into her system—engineered an engaging smile, and wrapped her hands about the doorknobs. She turned them and thrust the doors wide. “Well, Father,” she said, “I’m home. Have you killed the fatted calf?”

After her speech there was nothing to be heard in the room but the sharp tick of the mantel clock.

Verity looked around. The table was not set for luncheon. Eugene Strable stood at the fireplace. Jonathan knelt at the hearth and was lighting a small fire of kindling and cedar. Cassandra stood at the French windows, fingering the drapery cord. Louise sat fidgeting at the head of the table.

They all continued to gaze at her without speaking.

“Is there a reason,” said Verity after a moment, “why you’re all dressed in black?”

2

Verity had not been a month old when her parents purchased the house. Margaret Hawke, employing her considerable taste and her greater fortune, found exactly the place to suit them in a moneyed, well-managed, and discreet neighborhood at the southern extremity of Brookline, Massachusetts. Boston was less than fifteen minutes away by automobile, and at night the clouded sky might be red with the city’s reflection, yet the setting was one of strictly European formality.

The oldest part of the house had been built in the early 1920s, in the French Provincial style. The façade was narrow, uninviting, private. The house stretched far back, and then turned left into an L. The grounds were a modest three acres, and neighboring homes had at least as much to boast; privacy was as much thought of in the area as fine views and the right gardener. In the front of the house vast chestnuts stood resolutely in a graveled parterre. In the summer these ancient trees masked the house entirely from the private road on which the property was set, and in the winter their stark, tan, leafless forms lent the place an air of well-bred bleakness. In the back of the house, however, were thick stands of spruce, maple, dogwood, and mimosa. In her first season there, Margaret Hawke planted five Japanese magnolias between the garage and the kitchen garden, to remind her of Marlborough Street, where she had grown up and where the magnolias bloomed in profusion every March.

A nine-foot cobblestone wall—constructed before zoning laws constrained fencing to a meager six feet—surrounded the property. An arced gravel driveway went right up to the double-door entrance of the house.

The formal rooms of the house were long, rather low-ceilinged, and elegant. The hallway floors were marble, and the walls were painted a soft gray. The living room was in blue and orchid, and Margaret Hawke had furnished it with pieces taken from her grandmother’s house in Back Bay. The room was stately but comfortable. There were a maple-paneled office and two walk-in cloakrooms—one for men and one for women—at the very front, and at the back, a large dining room with a carved marble fireplace and three sets of French windows opening onto the back lawn; its walls were painted with the scenery of the upper Charles River. This entire floor, with suitable decorations, was prominently featured in the Christmas issue of Architectural Digest for 1965.

Two guest rooms and the master bedroom suite were located above this formal part of the house.

The stem of the L contained the kitchen, the breakfast room, and the servants’ rooms—it was thought innovative in 1922 to have the servants sleep on the ground floor. Upstairs were the four bedrooms, playroom, nursery, and three baths in which the three Hawke children were brought up.

Jonathan now lived in Back Bay, in a condominium in one of the Prudential Center residential towers. His father had gotten it for hi

m at a ridiculously low price. Cassandra still occupied the bedroom she had had since infancy, and Verity’s, at her father’s order, was kept always in readiness—with weekly airings and changing of linens—against her unexpected but always hoped-for return.

Two of the family’s boats were kept in the garage, and the third space was taken up by Richard’s Mercedes. Jonathan’s yellow Porsche, Cassandra’s black Audi, the Buick station wagon that was kept for the use of the servants, and Louise’s lime-green Toronado were often arranged in a curved line along the gravel drive. The keys to all these vehicles were kept in a basket on the table in the front hall, so that the cars could be used or moved about at will.

The entire household worked that smoothly. There were dates, inexorable as Christmas, when the winter drapes were taken down and the summer drapes put up, when the gardener was sent down to Truro to open up the summer house, when the iron garden furniture was repainted for the coming season, when furs were taken out of storage for the winter. All this was now Cassandra’s province. Richard rarely concerned himself with the workings of the house, but turned his energies to the running of his prestigious Newbury Street realty office. In colder months he often worked well into the night and on weekends. Late spring through early autumn, his spare time was devoted to navigating his sailboat along the upper reaches of the Charles River. To his children, Richard Hawke was a polite handsome stranger who knew a lot about winds and tides and each year at Christmas took them to the Boston Ballet’s production of the Nutcracker.

The relationship of the Hawke children to their late mother had been no less distant. Verity, Jonathan, and Cassandra had spent their first years under the loving care of a nurse and governess. Their mother they remembered best appearing in the bedroom door, kneeling to kiss them, smiling—and saying good-bye. The only time that Margaret Hawke spent six consecutive months in the house was the last year of her life, when she was confined to her bedroom with the cancer that killed her. When she died, Verity was eleven, Jonathan ten, and Cassandra eight. At her funeral none of the children displayed any emotion over their loss. Not long after, Verity and Jonathan were sent off to private schools in Vermont and New Hampshire. Cassandra followed them within a year. Verity, who eventually went to Bennington, was a fine student, and would have been a brilliant one if she had only applied herself. Jonathan was best in the sciences, and eventually graduated cum laude from Harvard, with a degree in anthropology. Cassandra went to Radcliffe and worked for a specialized major of comparative literature. She managed to graduate summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa. After college Verity and Jonathan had returned, at least for a time, to the mansion in Brookline. But with their father they maintained relationships of only the politest forms of affection. Verity moved out at the time of her marriage and did not return when the marriage broke up. Jonathan left following a terrible argument with his father, begun around a disagreement on what shoes to wear to church. For the past year Cassandra had lived alone with her father, but without any increased intimacy.

Wicked Stepmother

Wicked Stepmother Blackwater: The Complete Caskey Family Saga

Blackwater: The Complete Caskey Family Saga Gilded Needles (Valancourt 20th Century Classics)

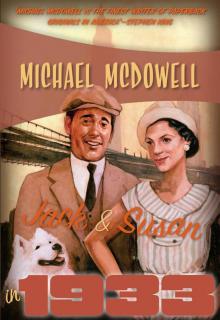

Gilded Needles (Valancourt 20th Century Classics) Jack and Susan in 1953

Jack and Susan in 1953 Jack and Susan in 1913

Jack and Susan in 1913 Rain

Rain Gilded Needles

Gilded Needles The Amulet

The Amulet Cold moon over Babylon

Cold moon over Babylon The Elementals

The Elementals Toplin

Toplin Jack and Susan in 1933

Jack and Susan in 1933 Katie

Katie The Valancourt Book of Horror Stories

The Valancourt Book of Horror Stories