- Home

- Michael McDowell

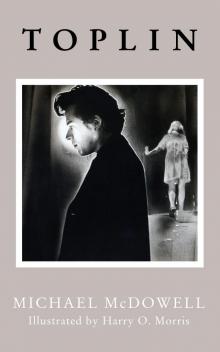

Toplin

Toplin Read online

Also Available by Michael McDowell

The Amulet

Cold Moon Over Babylon

Gilded Needles

The Elementals

Katie

TOPLIN

A Novel by

MICHAEL McDOWELL

Illustrated by Harry O. Morris

VALANCOURT BOOKS

Dedication: For A.

Toplin by Michael McDowell

Originally published by Scream/Press, Santa Cruz, Calif., 1985

Reprinted by Dell Abyss in 1991

First Valancourt Books edition 2015

Text copyright © 1985 by Michael McDowell and Charles Santino

Illustrations © 1985 by Harry O. Morris

Published by Valancourt Books, Richmond, Virginia

http://www.valancourtbooks.com

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the copying, scanning, uploading, and/or electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitutes unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher.

Cover illustration by Harry O. Morris

Errors disappear like magic. — Carton

This work is based on characters and basic story devised by Charles Santino.

It could not and would not have been written without him.

MMM

1

The grocery store was closed.

I hadn’t expected that. I had passed that grocery store every day for I couldn’t remember how many years, and it had never been shut at this hour. I had passed it every day on my way to work, and every morning it was open. It was open every evening on my way home from work. I never shopped there. I didn’t like the looks of the place. But that evening in May, I needed a particular spice, and that store—I was unutterably convinced—carried it.

A sign on the door read:

DEATH IN THE FAMILY

BUT COME BACK SOON

I didn’t believe it. There was something about the wording, something about the lettering that led me to believe that the shop was closed for some other, and very likely more sinister, reason. I couldn’t help but feel that it was closed because of me. After all, I had passed it dozens, hundreds, thousands of times, and never wanted to go in before. That particular day in that particular year I wanted to go in, and it was shut.

Not only was I certain that the placard was meant especially and entirely for me, I knew that behind it was a condescending, derisive laugh. Figure it out the sign said with a shrug of its painted shoulders. Determine why.

I peered through the window. I remembered the owner, in his black pants and his white apron. I had glimpsed him through the window before. I peered through the glass. I had the feeling he was hiding behind the counter. That he ducked behind the slicer when I peered through.

I could see nothing. The lights were off. The two narrow aisles were empty. The clock on the wall gave the incorrect time. I suspected the owner, in an attempt to simulate a real closing, had unplugged his clock. I wasn’t fooled. I knew that a funeral was an insufficient reason for holding back time. If there had been a real death in his family, he would have left the clock plugged in. Being greeted by the correct time on his return from the funeral would have provided consolation for the demise of his loved one.

I didn’t trust the sign at all. I stared through the window for several minutes. The owner was fat and wheezing, and I knew he’d be uncomfortable crouching behind the meat counter. If I only waited long enough, he’d have to stand up and stretch his legs. I waited, but he was more patient than I. Or perhaps, I thought, he had a camp stool behind there.

Not wanting to be tested by a man who was obese and asthmatic, I decided that I wouldn’t play his game. I walked off, inwardly vowing that from that day on, I’d take a different route to work and a different route home from work. He could keep his shop closed forever, on the same pretext, and I’d never know it. All his violent subterfuge would be wasted. I and my life would be unaffected by his crude stratagems.

There wasn’t another grocery store between that one and home. I’d have to travel to another neighborhood to find my spice. Perhaps that was the object of the sign, I thought, to send me to another neighborhood. I wouldn’t take the bait, I determined. I’d get along without the spice.

I couldn’t get along without the spice. Recipes are followed exactly. I had had this recipe picked out for a long time. I wasn’t going to give it up, and I wasn’t going to do it half-heartedly. I walked on toward home, though I was no longer certain that that was my destination.

Something in the neighborhood scented danger to me. It never had before, though on occasions, danger had been near and real enough. It’s an old part of the city, seen better days as they say, wasn’t likely to see better ones for some time to come, dilapidated brick and brownstone, old shopfronts, tenements burned-out or at best only run-down, with a population of old Europeans arrived in this country before their own nations turned Communist, still speaking the old languages, still looking as if they had awakened this morning in Krakow, and Prag, and Bucharest, and Kiev. Uninterpretable signs are everywhere, and you rarely understand the curses with which you are cursed.

I smelled danger. I saw two cars in a chase down a side street that was littered with children. I saw a string of parking meters that had been torn apart for their nickels and dimes. A young man and a young woman turned smoothly away as I approached—that smoothness that spells illicit drugs. I saw a drunk lying in the street, employing the curb as a pillow, screaming imprecise imprecations at every vehicle that passed. As I went by a pharmacy, a woman ran out screaming “Go to Hell! Go to Hell!” She wore a stained green slicker, army surplus boots, white socks, and a shapeless hat. A Negro, well over six feet tall, ran out after her and caught her when she became wedged between the bumpers of two parked automobiles. When he lifted her up, she kicked at him and at two more men—pharmacists by their white smocks—who rushed out of the shop. One she caught in his testicles, and the other’s wrists she bit savagely. “Give it back! Give it back!” they shouted at her, and as I went on toward home, no longer certain that that was my destination, they dragged her back into the store.

I was suddenly aware of a vagueness that had been troubling me for some time. It arched and peaked in that narrow avenue I trod, that avenue that stank so palpably of danger. I felt out of kilter. These were the streets I walked home along every day, without fail, without variation, without sensation. And now, on this particular day in May, I was suffused with the sense that everything was quite changed, that everything had been taken up into the sky and some verisimilitudinous copy had been set down in its place—and all for my benefit.

I decided I wouldn’t go home.

I’d eat out.

I never eat out. I have an unlimited file of recipes and therefore no reason to eat out.

I decided to eat in the restaurant that is at the corner of my own block, across from a derelict little park where people gather to drink cheap wine and settle drug deals. It’s so unhealthy that even the pigeons shun it.

I pass the Baltyk Kitchen twice a day, six days a week, on my way to work and on my way home after work. I’d never been inside, and I’d heard about it from a man who lived in my building. He moved out one night very suddenly, and when the landlord came to clean the place up for the next tenant, he found the lodger’s mistress in the closet. She’d been dead for two weeks. The windows of the Baltyk Kitchen were small and covered with sun-faded cafe curtains that might originally have been red, or perhaps purple. With my eyes the way they are, it was difficult to know. I didn’t know w

hat it was like inside—except for the narrow glimpse I’d get in the summer when the outside door would be propped open.

It’s only one room, square and not very large. There’s a bar along one side, and booths along the other, under the faded cafe curtains. In between there’s a white tile floor and half a dozen tables. On each table there’s a plastic carnation in a plastic catsup bottle.

It was already night in that place, though outside the sun was not even within an hour of setting. It was always night in the Baltyk Kitchen, I supposed. The place was open twenty-four hours a day, but between two and three a.m., it didn’t serve liquor, owing to some catch in the city alcohol licensing regulations. Regulars bought three beers just before two a.m. and nursed them until the bar opened again at three.

I went to the bar and sat down. I don’t drink, I don’t need to. There was no waitress, no bartender. I reached over and took a menu and opened it, but it was in a language I didn’t understand. I laid the menu open in front of me and looked at the pictures on the wall. There were photographs of European film stars, none of whom I recognized. There was a portrait of the Pope, with a border of carnations painted on the outside of the glass in the frame. There were travel posters, in bleached Agfa-color, aggrandizing the Warsaw Pact nations.

No one occupied the booths or the tables in the center of the room.

On one side of the bar, to my left, sat a middle-aged woman, neatly and respectably dressed, reading a paperback book. The remains of a meal had been pushed to one side.

On the other side, to my right, sat three men—truck drivers or stevedores wandered away from their docks and wharves, I surmised—each with a bottle of beer before him. Two of them had their heads down on the bar and were snoring. The third tilted his bottle slowly toward the ceiling and allowed a stream of pale anemic beer to drain into his mouth. He looked very drunk and very tired.

I waited and looked at the menu, trying to make out cognates.

The third man finished off his beer and laid his head down on the bar. Smoothly, as he did so, the second man wearily lifted his head, looked about blearily, and tilted his bottle slowly toward the ceiling. A stream of pale anemic beer drained slowly into his mouth.

They were guardians of the place, I decided. Two slept while the third kept drowsy watch.

The respectable, middle-aged woman on my left slowly and deliberately placed her book down on the bar, wiping the marble surface clean with a napkin before she did so.

She crushed the napkin and dropped it in her coffee cup. She swivelled her head and looked around. Only I and the three guardians were to be seen, but perhaps she was looking for someone else altogether.

“My husband was attacked by four hundred men!” she screamed at me. “He’s dead.”

I didn’t say anything. Whether she was telling the truth or not, there was nothing to say.

She picked up her book again and diligently searched for her place. When she had found it, she merely set the book down again. “That was a year ago!” she shrieked. “He’s dead!”

Still I said nothing.

“If he wasn’t dead,” she screeched, “do you think I’d be spending my evenings in a dump like this?”

I would have said something to her, but at that moment, as if the middle-aged woman’s rhetorical question had been her cue, the dingy curtains that hid the tiny kitchen at the back were parted, and the waitress came into the room.

Suddenly, with a blinding clarity, I understood where all that evening’s surprises had tended. The sign on the grocery window, so obviously false and contrived; the violence I had witnessed in the streets on my way toward my home; the peculiar slant of the evening sun which had convinced me that, against all habit and inclination, I should eat in the Baltyk Kitchen—all these things had propelled me to this place, this very stool on which I sat uncomfortably perched, at this particular moment of that particular day in May, only so that I might witness that waitress pausing in the deceptively simple motion of pushing aside the grease-stained linen curtains that hid the kitchen of this grimy restaurant.

It was the right and proper beginning of everything that was to come after. An entirely new phase of my life began at that instant. I—that is to say, my life up to that moment—died. I—that is to say, my life beyond that moment—was born.

I see that now. I did not understand it then. Then, I felt something else, something quite different.

I felt trapped in that instant, in that first moment of seeing her framed there, her hands behind her grasping the hems of that curtain, her stance taut and suspicious as she glanced over the restaurant and as her eyes fell upon me and lingered.

All those mercurial changes in pattern that I had noted that evening on my unsuspecting journey home from work had been arranged for the sole purpose of driving me into the Baltyk Kitchen, where I had never been before, in order to see this woman, of whose presence so near me, of whose very existence, I had been totally unaware. I had fallen into a trap and, involuntarily, I glanced toward the door and plotted my escape.

In the lurch to the door, I told myself, I might overturn a table. If so, I would not hesitate, wondering if I should right it. I would simply flee the place.

I did not flee. Her gaze held me.

She was, quite simply, the most hideous human being I had ever seen.

The disfigurements of her birth were compounded with the ravages of disease. I saw them in her face. Her mouth was a running sore. Her bulging eyes were of different colors. Her ears were slabs of flesh pillaged from anonymous victims of accidents. Her nose was a bulging membrane filled with ancient purulence.

I dragged my eyes away from her face.

Beneath her uniform I sensed—I smelled—even greater deformities. Her uniform, stained to a filmy translucence by God knew what manner of excretions, showed the irregularities of her skin beneath.

I looked away, gasping for my breath.

One of the sleeping guardians to my right raised his head and began to laugh, drunkenly. He turned to his friend who was already awake and asked, insultingly, “Why did Jesus Christ of Nazareth never eat pussy?”

His friend shook his head.

The riddler punched the third guardian awake.

“Because,” he shouted, “every time he touched one it healed!”

The three guardians laughed, and I turned desperately away from the waitress, who was filling a glass with water. I knew it would be for me. I turned up the collar of my jacket, and my head shrank inside it.

The respectable-looking woman put down her paperback book once more and shrieked at me: “Don’t do that! You won’t cut out the noise that way! Look at what I use!”

She jumped onto the stool nearer me. I wouldn’t have thought her capable of such spryness. She lifted the bands of white hair at the sides of her head and revealed large gray earmuffs. Their fur was stained and matted. I saw the rusted steel band that circled her neck.

“It keeps out all the noise!” she shrieked. “I can’t hear traffic! I can’t hear what they say to me! Wear these!”

She ripped off the earmuffs and flung them at me.

I caught them and placed them on the bar beside the glass of water the waitress had brought. My hands twitched and trembled.

I looked into the waitress’s eyes, willing their difference in color to be resolved. They remained obstinately different. I did not dare look anywhere but at her eyes.

The basilisk withdrew.

I stared down at the menu again and would not look up.

The respectable woman gathered up her earmuffs, and with her paperback book thrust high up underneath her arm, departed. I heard her shoes scraping grittily on the tiled floor. I was alone with the three drunken guardians and the gruesome waitress, staring at a menu I could not comprehend.

As I sat, staring at the menu, not daring to look up or turn around or even to run, I thought of her life. It was—it must be—insupportable. Such an appearance precluded any sort of natural intercourse

with other human beings. A walking aberration this young woman, so horrible that pity withered before her.

I was awed by her. Her ugliness filled me with a sense of urgency I had not felt for a long while. A degree of urgency, it occurred to me as I turned it over in my mind, that I had never felt before.

She stood before me, not two meters away, but so steadfast was I in my resolution not to look at her that I began—in the safety of my refusal to see her again—to examine, detail by detail, her loathsomeness as it was burned into my brain. I would pick apart her physical horror. I began with the feature that had first captured my single attention—her eyes.

Perhaps one of her eyes was a glass eye, I considered. That would account for the difference in color. Yet how much of a difference was there, really, I wondered. My sense of color is dim and has been for some time. I don’t see what others see; or at least I perceive that I don’t. At that moment, I longed for my old visual acuity to return. I wanted, for no motive other than to look at her eyes, to be able to distinguish the palette of light as I had once been able to, as everyone around me was able to. To me, one eye appeared brownish-green, one eye appeared brownish-violet. A cheap oculist, I considered. He gave her a glass eye that didn’t properly match her real eye that remained.

So certain was I of the validity of this hypothesis that I began to postulate in what sort of accident she had lost her eye. Was it an impalement, a searing, a disease, a self-inflicted wound? Had her eyeball soured, had it burst, had it been scooped out, had it simply ceased to exist one morning when she woke in her narrow bed?

I glanced up quickly. She was staring at me. I tried to look at nothing but her eyes. I wanted to test my hypothesis.

One eye must be glass.

Wicked Stepmother

Wicked Stepmother Blackwater: The Complete Caskey Family Saga

Blackwater: The Complete Caskey Family Saga Gilded Needles (Valancourt 20th Century Classics)

Gilded Needles (Valancourt 20th Century Classics) Jack and Susan in 1953

Jack and Susan in 1953 Jack and Susan in 1913

Jack and Susan in 1913 Rain

Rain Gilded Needles

Gilded Needles The Amulet

The Amulet Cold moon over Babylon

Cold moon over Babylon The Elementals

The Elementals Toplin

Toplin Jack and Susan in 1933

Jack and Susan in 1933 Katie

Katie The Valancourt Book of Horror Stories

The Valancourt Book of Horror Stories