- Home

- Michael McDowell

Jack and Susan in 1953 Page 2

Jack and Susan in 1953 Read online

Page 2

“Could you…” she began, and seemed to lack the strength to finish the question, so fearful was she of a negative reply.

“Yes, of course, I could,” he said, with a gallant half-bow in his chair.

“Tonight?” Libby asked, her eyes ablaze.

“By all means, if…” replied Rodolfo, looking across the table at Susan Bright.

“Why not?” said Susan.

Jack was by no means convinced that this was a good idea, but he did not object. “Yes, why not?”

“Oh, good-good-good-good-good,” burbled Libby. “This is going to be an evening to remember.”

CHAPTER TWO

AFTER THAT, LIBBY’S undisguised anxiety to leave was amusing to Susan. She had been in other restaurants with Libby Mather, and she remembered that Libby always ordered two desserts and nibbled off of everybody else’s plate as well. But now she was foregoing dessert altogether, announcing that the Baby Ruths in her bag were perfectly sufficient. “Get the check,” Libby said to Jack in a low insistent voice.

Once the bill was obtained and paid, the two men got up and fetched coats.

Libby leaned over toward Susan, and whispered—though whispering was hardly necessary—“He’s so handsome. Does he use something on his skin?”

“I beg your pardon?” Susan returned, not understanding.

“To lighten it,” explained Libby. “I wouldn’t have known he was Spanish until I heard his name. I’ve heard that the first thing Spaniards do when they get off the boat is invest in a case of lightening creams.”

“Rodolfo is Cuban,” said Susan. “Havana? The gambling casinos? Remember? And so far as I know, he doesn’t use lightening creams—if there are such things.”

“Well,” said Libby thoughtfully, “maybe he’s a half-breed.”

Libby was pleasant to Rodolfo, though that had more to do with the fact that he knew the whereabouts of a gambling den, than it did with any real sense of politeness. They found a cab a few doors up from Charles’, and all crawled in the back. The two men were on the outside, with Susan and Libby squeezed together between them. Libby wouldn’t hear of anybody sitting in the front. She maintained a belief, which she stated quite loudly, that all cabdrivers were infested with fleas picked up on trips to other boroughs.

Retaliating, the cabdriver deliberately took the long way and drove into Times Square. It was half-past ten, and the sidewalks were thronged with people. Beneath the enormous brightly lighted marquees of the Broadway theaters, well-dressed crowds were milling about and talking and making supper decisions and keeping eagle eyes out for empty taxis. Polite lines had formed in front of Longchamps and Lindy’s, and teenagers in open-topped cars shrieked with laughter and waved at the pedestrians. At Broadway and Forty-fourth Street the cab became embroiled in a massive jam of cars and pedestrians. This gave Libby the chance to launch once more into a stream of chitchat.

Libby’s arm pressed against Susan’s ribs. Libby’s arm was firm and fleshy, just like the rest of her. She wasn’t fat—she wasn’t even plump—but Libby had flesh where men thought a young woman should have flesh. Libby had curves that gave her a silhouette enticing from the back as well as from the sides. Susan, on the other hand, was slender. No curves. Enemies—and Susan herself—sometimes pronounced her figure bony, but in better moments Susan knew that wasn’t the case. She just didn’t have flesh to spare. She hoped she’d be around when—and if—thinness and flatness came into style once more. When was the last time? Susan wondered. Oh yes, the twenties. Her mother’s generation. Well, maybe if Susan herself gave birth to a daughter tending to thinness, the eighties would be kind to the girl.

Susan was also annoyed by the fact that the young woman chattering in her ear always managed to dress in the teeth of fashion. It was a talent Libby had, of always looking as if she’d just walked out the door of a smart avant-garde shop. It was a discouraging habit, as far as Susan was concerned. Sometimes Susan tried to dress in the teeth of fashion as well. She would spend more than she ought on clothes that were exactly right; would take them home, and put them on and look at herself in the mirror, and know that at that moment she stood at the pinnacle of style. Then she’d go downstairs, and by the time she got to the street, the avant-garde style would be old hat, and every secretary in town would be wearing Susan’s outfit. At a restaurant or nightclub Susan would see where she’d made her mistake. The new color today was red, not violet. The covering for the head was a tiny feathered helmet, not the wide-brimmed toreador hat with ball fringe that she had purchased with an impulsiveness she had regretted almost immediately. With a little inward sigh of despair, she would admit to herself that she’d probably never be on the cutting edge of modern fashion.

Before Susan could elaborate mentally on further differences between herself and Libby Mather, the taxi began to move. In another five minutes they pulled up in front of an ordinary-looking brownstone on East Fifty-fifth Street between Park and Madison. They climbed out, and Jack paid the driver.

Drawing her arm through Susan’s, Libby leaned over and said, with evidently unfeigned relief, “Oh Susan, I feel so much more comfortable uptown, don’t you?”

Only two minutes earlier Susan had told Libby that she was living in an apartment on the east side of Washington Square.

Whatever reason Jack had for seeing Libby, Susan wished him joy in the company of her old friend.

Mr. Vance’s establishment—it had no other name—was located on the upper floors of the brownstone. On the ground floor was a small restaurant wholly inadequate to accommodate the considerable number of well-dressed persons who tried to get through its front doors. But in the lobby of the restaurant was a door leading to a narrow curving staircase that wound up to the second floor. At the top of these narrow steps was a wide door padded in red leather. It wouldn’t open for Libby. She peered into the diamond-shaped mirror on the door and said, “I bet there’s somebody behind here. I bet this is a three-D mirror.”

“Two-way mirror,” Jack corrected.

“May I?” said Rodolfo. Jack pulled Libby out of the way. Rodolfo stood directly before the door and tapped with his knuckles on the mirror. Almost immediately the door opened. The doorman was dressed in an ill-fitting dinner jacket that plainly outlined a shoulder holster beneath his left arm. Perhaps, Jack considered, that visibility was intentional.

Libby swept in and immediately declared herself enchanted. The carpet beneath her feet was deep and red; crimson damask draperies closed thickly over tall windows. Even the two ladder men who oversaw the room’s gambling operations were seated on high platforms lacquered Chinese red. The floor–through establishment boasted two craps tables, three blackjack tables, and a roulette wheel in the far corner. The clientele was well heeled, if not precisely fashionable. While the men checked their coats, Susan sized up the room; she saw lots of expensive clothes and what appeared to be diamonds. The ladies looked as if they had paid for their adornment—one way or another. All the gentlemen seemed to be wearing new blue suits of a style comparable to Rodolfo’s.

Libby didn’t even glance at the other gambling tables as she made a beeline for the roulette wheel, Jack tagging behind.

As they made their way across the room, Libby abstractedly reached into her pocketbook and brought out a small wallet. “This is all I have,” she said with a hasty sigh, as if she were too busy to spare a longer one. “Jack, be a darling, please, and go get me some chips.”

Jack looked around, and Libby—who didn’t appear to have noticed anything in the room except the roulette wheel—pointed toward the opposite corner with exasperation. “Over there, you silly,” she said impatiently. “Over there.”

Over there consisted of a tiny, dark triangular booth half hidden behind a screen in one corner of the room. In it sat a man in a tuxedo whose eyes were so heavy-lidded he appeared not to have slept for days.

Jack put the money on the counter, and said, “Chips please.”

“Yeah?”

/> “Yes, what?” asked Jack. Jack had just decided that he didn’t like this place, and when Jack Beaumont didn’t like a thing, his voice became short and surly. It was sometimes a disadvantage not to be able to disguise his feelings, and Jack had scars to prove it.

“Yeah what kind of chips. Fi’-dollar chips, ten-dollar chips, hunnert-dollar chips, or what—what kind of chips I’m asking is what I’m asking.”

“Five-dollar chips,” said Jack. He objected to the obvious illegality of the operation and distrusted the aspect of the men who were hired to run it. But most of all, he was forced to admit, he didn’t like the fact that it was Susan Bright’s companion who had brought them there.

As it happened, Libby Mather was further indebted to Mr. García-Cifuentes for an introduction to the roulette croupier, and was standing quite close to Rodolfo at the edge of the table, anxiously awaiting the arrival of her chips. “You are so slow, it makes me furious,” Libby complained as Jack approached. “I could have made five hundred dollars in the last ninety seconds. How much are these worth? How much money did I give you?”

“These are five-dollar chips, and you gave me two hundred dollars,” said Jack. “Why on earth do you carry around so much money, Libby?”

“In case I’m asked to elope,” returned Libby archly, “I want to make sure I have decent shoes for the wedding.” She lurched forward and placed ten of her chips, which were red, on black.

Though he had not gone to the cage in the corner, Rodolfo had chips as well, and Jack wondered for a moment where he might have gotten them. Was he such an habitué of this Mr. Vance’s establishment that he carried them about in his pocket at all times? Rodolfo was working with ten-dollar chips and was betting on even, as well as directly on the number twenty-seven.

Jack stood behind Libby and was watching as the croupier spun the wheel in one direction and snapped the small white ball into its trough, sending it around in the opposite direction. “It’s very bad luck to have someone standing over your shoulder at a roulette wheel,” Libby said severely.

“I just thought I’d watch and see how it works,” Jack returned mildly.

“I’ll buy you a book,” said Libby. “I don’t have time to teach you. Now go away. Rodolfo,” she went on in a whisper, “ask the croupier how the table’s been going tonight. Has it been running black or red?”

Jack backed off, and headed for the bar that ran down one long side of the room. Susan was seated on a stool at one end, looking a little self-conscious, as women sitting at bars alone often did in 1953.

“Rum Collins,” Jack told the barman. With the memory of how he and Susan had parted four years before, it was with some apprehension that Jack turned to her and remarked, with as much inconsequence as he could muster, “We’ve both been abandoned, it appears.”

“I haven’t been abandoned,” said Susan. “I just have no interest in gambling. Of course, I had no idea that Libby was so…”

“Yes?” Jack prompted. For the first time Jack could smell the perfume Susan was wearing. It startled him. Lilacs.

“…enthusiastic,” said Susan. “About roulette.”

“I didn’t know either,” returned Jack. “Has Rodolfo brought you to this place before?” He looked about with an air of unsettled mistrust. What was that perfume called?

“I’ve never been here,” said Susan. There was an evasiveness about her answer that piqued Jack’s interest.

“At the restaurant,” he said, “you did look surprised when Rodolfo mentioned it.” Duchess of York. White lilacs. He’d bought Susan Duchess of York perfume their last Christmas together. She was still wearing it—but for another man. Very annoying.

Susan paused only a moment before answering. “Rodolfo hasn’t been in New York long. I’m always surprised how well he can find his way around. It takes most people years.”

“You’ve been showing him about?” asked Jack with a pleasant smile.

“Rodolfo is a friend of the family,” replied Susan shortly. Then, with a smile as pleasant as Jack’s had been, she remarked, “You know I was a little surprised to see you at the restaurant with Libby.”

“Really?” said Jack. “What was so surprising about it?”

“Well,” said Susan, “I had heard that you’d married a New Orleans demimondaine and that she attacked you at the reception with a cake knife when she found out that you’d made her maid of honor pregnant.”

“Sorry,” Jack replied after a moment, swallowing his anger to see what it would turn into. It turned into quiet sarcasm. “It wasn’t quite like that. I’d gotten the bride’s mother pregnant.” Jack lifted his head and rubbed his neck with two fingers.

At this meeting, their first in four years, Susan could have been coldly polite and distant, to indicate how little she cared for him now. Instead, she chose an undisguised attack, showing that her animosity was still very much alive. That was interesting, Jack decided, but he couldn’t make any more out of it than that. Susan shook her head. “Isn’t it strange how the truth gets distorted?” Susan briefly pondered whether she should jump down off the barstool and stalk away. Jack’s mistrust of Rodolfo was apparent. His questioning of her was rude, and he ought to be punished. But if she did jump down, and in the process manage to land with her spike heel on Jack’s foot, where in the room would she go? She stayed where she was.

“Yes,” said Jack. “It is strange what passes for truth these days. For instance, I’d heard that you’d married a senator’s son and moved to Washington, but that he’d abandoned you for a Brooklyn laundress. I felt so bad I nearly wrote to you. I wouldn’t have believed it to be true, but so many people came to me with the story…”

“No,” said Susan, looking into her glass, nearly empty. “I haven’t accepted any proposals of marriage lately.” She waved to Rodolfo across the room.

“And I haven’t made any.” Jack smiled in the direction of distant Libby. “Not this week anyway.”

Susan Bright signaled the bartender for another drink. “And I wouldn’t either, if I were you. At least not till you’ve learned to take a little better care of yourself. Has that suit been pressed in the last year? Or cleaned?” she added, peering at the spot on the front. “I see your hair has continued to recede. Have you considered the advantages of a toupee?” Susan knew she was touching a sensitive point. Jack had straight brown hair that he combed straight back. Now that his hair was thinning in front, his forehead—always high, broad, and unlined—seemed even higher and broader. But that brow lent him a certain nobility of expression and a suggestion of intellect—at least when he was in repose. His face was sculpted, with a sharply defined jaw and high cheekbones, giving him an enormous expanse of shaven cheek. Susan had always thought him handsome, but she knew that Jack had always felt his features were too angular. Though, so far as Susan was concerned, the features of a man’s face could never be too distinctly defined. “Or perhaps,” she went on, “you’re just worrying too much about what it would be like to be married to a margarine heiress…”

Jack suddenly stood up straight. He cast a cold eye on Susan. “The intervening years haven’t dulled your tongue. Don’t start in on Libby, and I won’t say anything against Señor García-Cifuentes.”

“I can’t imagine what you could say against Rodolfo. Sometimes I think he’s the only real man I’ve ever met.” She looked at Jack meaningfully.

“I have nothing to say against Rodolfo personally,” said Jack, paying no attention to the insult, “but I have been wondering about his friends. Do they all have such heavy jowls? And such dark beards? And smell of bay rum? And carry guns?” Jack nodded around the room, at the doorman, the croupiers, and the tuxedoed ladder men perched on their platforms like overfed penguin lifeguards.

“These aren’t Rodolfo’s friends,” said Susan. “Rodolfo just knows them. Rodolfo likes to gamble—all Cubans do, I’m told. He told me his entire Harvard education was paid for by his mother on a winning lottery ticket—you know, the Havana lotte

ry.”

“I don’t remember him from Harvard,” said Jack. “And since we seem to be about the same age, we would have been there about the same time. Are you certain—”

“Neither Rodolfo nor I can be responsible for your memory, Jack, any more than we can be responsible for your extraordinarily peculiar taste in female companions. Libby has one of the most—”

Susan left off abruptly, and for a woman who never blushed, she came very near it at that moment. Jack turned to see what had interrupted her, and found Rodolfo standing directly behind him. Jack wondered for a moment how long the Cuban had been there, but if he’d heard any of the conversation, he gave no indication. He said, “Mr. Beaumont, I think you’d better see to Miss Mather. She’s…”

Jack immediately moved away from the bar to a position that gave him a clear view of the roulette wheel. But even before he could see Libby, he heard her voice, strident as only Libby’s could be: “That’s the fourth time in a row! That doesn’t—”

Jack moved toward Libby and, glancing back over his shoulder, saw Rodolfo and Susan conferring. In seconds, Jack reached the roulette table. As before, perhaps a dozen persons were gathered around. The ball was spinning, but not a single bet had been placed on the board.

Libby spoke loudly. “I’m not betting. And I’d advise everybody else here not to bet.”

“Make yer bets,” said the croupier. “Make yer bets, please, ladies an’ gen’men.”

“Don’t,” Libby advised the company airily. “That’s four times in a row that the zeros have come up. Four times.”

Jack reached her side. “Libby,” he said quietly, “what’s the matter? I could hear you all the way across the room.”

“Then you know what the matter is,” she said. “The matter is that I’ve only got two damn chips left because this wheel has landed on zero or double zero four times in a row, and it’s fine for me because that was mad money for my possible elopement and nobody’s made any proposals of marriage yet tonight, but these other people are losing lots more money than I am—”

Wicked Stepmother

Wicked Stepmother Blackwater: The Complete Caskey Family Saga

Blackwater: The Complete Caskey Family Saga Gilded Needles (Valancourt 20th Century Classics)

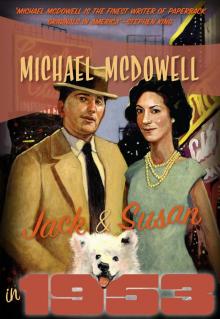

Gilded Needles (Valancourt 20th Century Classics) Jack and Susan in 1953

Jack and Susan in 1953 Jack and Susan in 1913

Jack and Susan in 1913 Rain

Rain Gilded Needles

Gilded Needles The Amulet

The Amulet Cold moon over Babylon

Cold moon over Babylon The Elementals

The Elementals Toplin

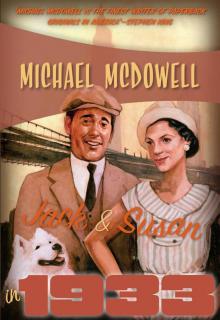

Toplin Jack and Susan in 1933

Jack and Susan in 1933 Katie

Katie The Valancourt Book of Horror Stories

The Valancourt Book of Horror Stories