- Home

- Michael McDowell

Jack and Susan in 1913 Page 2

Jack and Susan in 1913 Read online

Page 2

Even from that distance of a dozen yards, and at night, in a driving snow, Susan could also tell that Mr. Austin was indeed the sort of gentleman to employ code words in notes sent backstage.

So Ida had been jealous—but Ida had also been right.

With a sigh, Susan Bright turned away into the snow.

Back at the entrance to the theater she ran into the show’s stage director, and several of the actors. This group was retiring to a small neighborhood restaurant to wait for the reviews, with a bottle or two or three of wine, and they asked Susan to join them. Without knowing exactly why she did so, she declined the invitation.

When this group had ambled out of sight, she pulled the veil of her hat over her face, just in case Mr. Jay Austin should come out of the alleyway. Susan crossed Eighth Avenue and looked up and down. She had decided that if she found a taxicab, she’d take it. With the moderate hope of several weeks of employment—she would be getting in excess of thirty dollars a week—she could afford the fifty-cent extravagance.

The streets were now filling up with snow considerably faster than the municipal authorities could remove it, and no taxicabs were to be seen. She could either walk home—twenty-two blocks—or she could walk to the subway station at Times Square. She decided that the subway was by far the wiser idea.

With Times Square as her goal, Susan headed straight across residential Thirty-eighth Street toward Seventh Avenue where she would turn north at the Hotel York. It was still a long walk through the driving snow, alone at so late an hour, a prey to footpads or likely to be mistaken for a prostitute.

Just then a small white dog—a wire-haired terrier—bounded down the sidewalk toward her, yapping ferociously, and diving into small snowbanks at the base of the streetlamps as if he thought rats might have taken refuge inside. The dog was obviously as delighted with the weather as Susan was inconvenienced by it, and that gave her a little perspective on the gloominess of her disposition. After all, this should be a night of celebration—an opening night, the possibility of weeks of work, a purse that was going to swell instead of shrink. Susan could not help wishing that Mr. Jay Austin had proved to be someone her own age, or perhaps a little older, comfortably situated, unmarried, and not predicating a friendship on her making certain amorous concessions. It was a great mistake on the part of the lay public, Susan thought, to imagine that theater people were any less lonely than the rest of humanity.

“Here, boy,” she cried with a snap of her fingers.

The dog ran up and leapt into the air, playfully snapping at her hand.

She caught him out of the air and hugged him and tossed him into a fluffy snowbank.

The dog burrowed down, shot back up again in a different place, ran around Susan three times, and leapt into the air again.

This play continued up the street as Susan made her way toward Seventh Avenue. If the collarless dog was a stray, then at least he was a happy stray.

At this late hour and in this weather the few people she passed were men, but she did not see their faces, they were so bundled against the driving snow. She knew that after they’d passed, they turned around and looked at her—a lone young woman on the snowy street at this hour. But Susan hurried along, laughing, with the white terrier.

As she rounded the Hotel York Susan became certain that she was being followed.

Just a feeling at first, confirmed a moment later by the noise of crunching snow in the silent city behind her. The dog, tossed into yet another snowbank, this time came up growling.

Susan quickly reached down and snatched up the animal. She shook the clumped snow off him; he was now all teeth and hot doggy breath. He dug his claws into the front of her cape, and climbed up her shoulder, snarling and growling at whoever followed.

Probably it was just another lonely soul like her, stranded in the snowy night, with no intention more sinister than getting home as quickly as possible.

The dog scraped and clawed, evidently with the intention of attacking the person who was steadily lessening the distance between them, but Susan held him tight. The dog was a weapon, and she didn’t want those ferocious jaws out of her hands.

The dog scraped, and barked, and clawed—and finally began to howl in his frustration. Susan moved along as quickly as she could, without seeming to run, without risking a fall on the slippery snow. She watched for cabs, for policemen, for sympathetic passersby. She was alone on the dark streets of Manhattan in a snowstorm, with a recalcitrant dog, and a dogged pursuer.

As she was crossing Thirty-ninth Street, the man stopped her with a hand on her shoulder.

The surprise of his touch loosened her grip on the terrier, and the dog flew over her shoulder and clawed his way through the air.

“Oh, Lord!” cried the attacker in a hoarse croaking voice, “Miss Bright—get him off!”

Susan turned, a bit less alarmed, but now confused. The man who’d been following her lay in the middle of the street—fortunately empty of traffic—keeping the terrier at bay with his feet.

“How do you know my name?” Susan asked, but just then she recognized her pursuer as the tall man in the third row and she knew the answer.

“I sent you a note this—”

“Yes, Mr. Austin. I looked for you—”

She grabbed up the terrier and held him close to her tightly to prevent him from making any further attack on her admirer.

“I waited for you outside the stage door. When you didn’t—”

“Oh, I didn’t see you. There was a fat man—”

“—waiting for Miss Conquest. She told me that you had already left, so I—”

“But I hadn’t—”

They didn’t seem to be able to finish a sentence properly, but it was a bit difficult to carry on a normal conversation, given the circumstances. On top of the fact that Mr. Austin was having some difficulty getting to his feet, and Susan was having even more difficulty in controlling the dog, from the croaking sound of Mr. Austin’s voice, he seemed to be on the verge of coming down with the grippe. Lying for long in a snowy street wasn’t going to help that very much.

But at least it was happily apparent to both that some sort of unintentional error had been made.

Mr. Jay Austin finally pulled himself to a standing position by grasping the fender of a parked automobile, took a breath and said, “You ought not be out alone, Miss Bright. May I see you safely to your home?”

The terrier, as if understanding this speech and objecting to it strenuously, made one more valiant lunge in the attempt to implant his sharp teeth into the man.

“Yes you may, Mr. Austin.”

It was very aggravating to Susan that she still couldn’t properly see his face. The snow was thick, the street was dark, the brim of his hat shadowed much of his visage, but she saw enough to allow her to hope that he was really quite handsome.

“You have a very rambunctious canine there,” he remarked ruefully.

Susan thought he would have taken her arm, had it not been for the dog. She would have put the dog down, but she was certain it would attack again. So they headed toward Times Square, a few feet apart, chatting as best they could in the intervals between threatening snarls and frigid gusts of snowy wind.

He had waited for half an hour at the stage door, and must have been there when she peeked into the alley. But because he was not standing in the light, they decided, or hidden by the overfed form of the man who was waiting for Ida, Susan had simply not seen him. He had finally given up hope and emerged from the alley when he saw a female figure, alone, cross Eighth Avenue and then disappear into the darkness. He’d followed hesitantly at first, unsure of her identity, but caught her profile when she’d once turned in the lamplight and lifted her veil—and now here he was.

“Your performance was entrancing.”

“You were in the third row. On the aisle.”

“You saw me!” he exclaimed.

“I saw you rip your jacket.”

“Now I’ve

ripped my trousers as well. It’s just as well that it’s so dark out.”

Susan fretted a bit as they walked. It was the middle of the night, she had accepted the company of a stranger, and she was an actress—would he expect more? Would he demand it? How could she show her interest in him without leading him to think that she often accepted this sort of attention—and much more—from gentlemen who waited at the stage door? It was difficult for a woman to meet a man on anything like equal footing, and now Susan’s years of independence seemed to melt beneath this daunting difficulty.

She was often lonely, and tall gentlemen who could afford third-row aisle seats—and who admired her acting to boot—were not easily come by. With that thought in mind, despite the weather, the wriggling dog in her arms, and the possibility that Mr. Austin was coming down with pneumonia, Susan deliberately walked past the entrance to the Times Square subway station and continued uptown, as if it had been her intention all along to walk all the way home.

Broadway would have been more direct, but Seventh Avenue was a quieter and longer route. Though recently many commercial buildings and hotels had sprung up in this area, there were still a number of brownstone houses that remained private residences. Despite the pleasure of the tall gentleman’s company, Susan was pleased that they were now quite close to her home—it was nearly one in the morning, the snow showed no sign of letting up, and the dog in her arms had not ceased his efforts to fly at Mr. Austin’s aching throat. She’d tried to put him down once, but snatched him up again as quickly as he’d torn the cuff from Mr. Austin’s right trouser leg.

Despite the lateness of the hour, there was more traffic in this area of the city, and several taxicabs now passed, making their cautious slow way through the slippery streets. Mr. Austin offered to fetch one of these for Susan, but she had declined: “I’m so near home…”

They were about to cross Fifty-eighth Street, when a long covered touring car came crunching toward them through the snow, its yellow headlamps creating cones of yellow light through the swirling precipitation. The automobile stopped near them and for several moments Mr. Austin and Susan were caught in the yellow glare. A chauffeur emerged, opened the rear door of the car, and a large man, wrapped in a vast dark fur coat, got out and started up the steps of the house on the corner.

“The Russian consul’s home,” said Mr. Austin, stopping at the curb, “and unless I am very much mistaken, that is the consul himself. I imagine he is quite used to weather like this.”

“How do you know—” began Susan, but her speech was abruptly cut off in surprise. For from around the corner lurched a scrawny, bearded man wearing a thin overcoat and heavy boots. Staggering forward through the snow, he shouted something in a strange language.

Coming to a stop almost next to Mr. Austin and Susan, the man produced from beneath his overcoat an object about the shape and size of a large melon, which he appeared to be ready to hurl at the man Mr. Austin had identified as the Russian consul.

At that moment, the dog made another lunge at Mr. Austin, and Susan’s companion lost his footing.

His legs flew out from beneath him, and he slid forward, colliding heavily with the bearded man.

The melonlike object flew straight up in the air, hovered there a moment, and then began to drop straight down.

Two things occurred to Susan as this was happening.

The first: The bearded man in the thin coat and the boots was an anarchist.

The second: The melonlike object that was spinning down through the air toward her was a bomb.

Its glowing fuse described a perfect parabolic spiral through the snow-laden air.

CHAPTER THREE

JAY AUSTIN HAD barely regained his footing on the sidewalk, when he saw the danger presented by the bomb. Without a moment’s hesitation, he threw himself bodily on to Susan, crushing her down into a soft bank of snow at the curb.

Protecting me, she thought, and then all thought—of the anarchist, of the falling bomb, of the dog squeezing out of her grasp, and of Mr. Austin’s selfless behavior—were flashed away by an explosion—an explosion of pain in her right leg, a pain of an intensity she’d never felt before.

Mr. Austin had completely covered her body with his, pressing her into the cold snow.

“Oooooff,” he said, and she felt him flinch when the anarchist’s bomb struck him a glancing blow in the small of the back.

She turned her head, brushing one cheek against the snow, and the other against the rough wool of her protector’s overcoat. She saw the sinister black device roll into the snow, where the fuse fizzled into nothing more than a stub of black charcoal.

“Please let me up,” Susan whispered—whispered because he was so heavy atop her, it was hard to get breath into her lungs. “The bomb didn’t go off.”

Mr. Austin raised himself and rolled over on his side away from Susan. He stood up, grabbed the bomb, and hurled it down the street as if it were a ball in a game of tenpins.

All this occurred in a matter of seconds. Susan, still lying in the snow, saw the Russian consul hurry up the stairs of his residence—experience probably having taught him not to wait around in order to satisfy his curiosity about certain altercations in the street.

At the same time, the chauffeur blew a shrill whistle, and called out imprecations and threats against the bearded anarchist, who had turned and was headed down the avenue at a trot.

“Anarchists!” shouted the chauffeur. “Anarchists!”

Windows began to be raised along both sides of the street.

The white terrier stood near Susan’s feet, looking indecisive. He seemed to be trying to decide whether to attack Mr. Austin again or to run after the anarchist.

He whined.

Susan threw out an arm and pointed down the block. “That one.”

The terrier barked happily, and at once dashed off in pursuit. At the corner of Fifty-seventh Street he caught up with the would-be bomb-thrower. Seeing his chance, the dog leapt on to the hood of a Pope Hartford touring car parked in front of the Osborne Apartments and then hurled himself on to the anarchist’s head.

The man screamed, and tried to shake the animal off.

The dog clawed and barked and bit, tearing at the anarchist’s face and neck.

Blinded, the anarchist stumbled to the right, knocking into a streetlamp. Then he stumbled to the left, slipping on a patch of ice.

Just as the anarchist at last succeeded in clawing the dog loose from his head, a police van approached the corner of Fifty-seventh Street—not with its siren on, but just on a routine middle-of-the-night beat. The anarchist held the dog aloft, screeching imprecations at it in Russian, then flung it into the street, right into the path of the oncoming vehicle.

Flailing helplessly, the little terrier tumbled end-over-end through the swirling snow and landed a couple of yards in front of the van.

The driver, seeing what had happened, instantly pulled the brake lever, causing the tires to skid on the snow and the vehicle to spin out of control. The animal tried to scramble to safety, but in another moment was caught beneath one of the turning wheels of the van.

The dog let out a howling yelp, but that pitiful scream was overridden by another—and a human one at that—as the anarchist, blinded by his own blood that had been scraped out of his forehead and scalp by the dog, was also struck by the out-of-control vehicle. With a terrible grinding, the anarchist’s legs and midsection were crushed against the lamppost; the impact of the collision was so great that the lamppost cracked in two and fell into the street across the roof of a taxicab.

As the police clambered out of their van and surrounded their unintended victim, Mr. Austin arrived on the scene and ran out into the street and grabbed up the battered but still-breathing dog. He walked back up the avenue to where Susan Bright still lay in the snow.

The dog whimpered in Jay Austin’s arms, and his attempts to bite the man were pitifully ineffectual.

“I think he’s broken his leg

,” said Mr. Austin sadly, and held out a hand to help Susan to her feet.

But she merely waved away the proffered assistance with a gesture of disgust. “So have I,” she said with dismal certitude.

Susan Bright, a young actress new to our stage (at least I cannot recall having seen her before), played the part of the heroine’s sister-in-law, and played it extremely well. She is a good, reliable, and interesting actress, with a certain amount of personality, and I should say that she will be a useful addition to our list of leading ladies—or perhaps I should make that “stars.” She lacks the original methods of a great actress, but has all the qualities of a good one. These are nice and comforting things to possess, and Susan Bright will be seen again—let us hope, in a more becoming frock.

She didn’t have the heart to read any more of the reviews, though the stage manager, who visited her in the ward at Bellevue Hospital, assured her that they were all very good. It was just her luck that on the night that promised to be the beginning of a long and prosperous career, she should suffer a broken leg.

And not only was her leg broken, but she’d learned that one of Ida Conquest’s friends took over the part of Daisy the following evening, and from all reports, was irredeemably dreadful. For her two weeks of intensive rehearsal, for all her hopes, and for all her plans, Susan received exactly seven dollars and twenty-five cents, a pro rata salary for one evening’s performance—a sum that was immediately consumed by the first night in the hospital.

What good were handsome reviews when you lay in bed with a broken leg? The doctor hoped she wouldn’t limp for more than six months, but of course you never could tell in cases like this.

“Cases like what?” Susan demanded.

“Broken legs,” said the doctor, unhelpfully.

After he’d done with the police, Mr. Austin came to the hospital, but Susan wouldn’t see him. She knew that the accident had not been his fault—that he really had been trying to save her life—but still, she could not help but feel that it was on his account that she had lost her part in He and She. In fact, if the limp were permanent, Susan would no longer have any future at all on the stage. Maybe Bernhardt could do it on a wooden leg, but it was an unwritten law among theater managers that ingenues needed their limbs intact.

Wicked Stepmother

Wicked Stepmother Blackwater: The Complete Caskey Family Saga

Blackwater: The Complete Caskey Family Saga Gilded Needles (Valancourt 20th Century Classics)

Gilded Needles (Valancourt 20th Century Classics) Jack and Susan in 1953

Jack and Susan in 1953 Jack and Susan in 1913

Jack and Susan in 1913 Rain

Rain Gilded Needles

Gilded Needles The Amulet

The Amulet Cold moon over Babylon

Cold moon over Babylon The Elementals

The Elementals Toplin

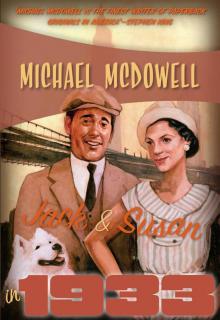

Toplin Jack and Susan in 1933

Jack and Susan in 1933 Katie

Katie The Valancourt Book of Horror Stories

The Valancourt Book of Horror Stories